“I was discontent . . . ,” he states. “. . . [S]o I just threw in the towel and took off.” For a South San Franciscan city boy, this was a monumental decision. Leaving behind his hard-won position as a color-tester at DuPont Paint, he partnered up with a fellow San Franciscan named Ed, purchased some hiking boots, and set out for New York.

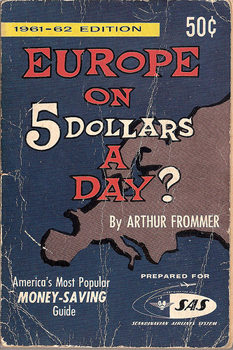

As he boarded a turbo prop plane to Iceland in February 1967, Dennis Del Greco embarked on a hitchhiking journey across Europe that would change his perspective on relationships and the world. Upon landing, Dennis relates how little he knew about travel – particularly the sharp contrast between European and Californian winters. “I got travel-wise real quick,” he admits matter-of-factly. He and Ed hastily journeyed south to England, then France and Spain. Armed with his travel bible, Europe in $5 a Day, Dennis adapted to seeing drivers on the left side of the road and taking speedy showers when charged for hot water by the minute.

While in Spain, Dennis visited Toledo: still a vivid memory though forty-six years have passed since his journey. He mounted the crest of a hill and looked down in wonder on “this City of Oz . . . in a valley surrounded by water.” Of particular interest was the home of the painter, El Greco, who shared a similar last name with the hitchhiker. Dennis commented in his journal that “I felt like this was my house . . . ,” when he read its designating plaque “El Casa Del Greco.”

Adventures in Africa

The hitchhikers’ next destination was Tangier, Morocco, but they were not permitted passage due to Dennis’ appearance. Although the grandfatherly Italian has since cut his thick, gray hair, at the time it was long and brown and accompanied by a beard (he still proudly wears a full one). In an age of clean-cut hairstyles, the twenty-six-year-old stood out unmistakably. When asked why he chose to wear his hair long, he replies lightly, “I don’t know; it’s just me,” – a subtle hint at his self-assured persona, which has never been governed by others’ opinions. Dennis recalls how, although his hairstyle and beard hindered him when attempting to enter other countries, they also proved helpful in procuring rides from curious passersby. He relates, “. . . [W]hen I went through a town, people would follow me like the Pied Piper, and windows would open, and people would stick their heads out the window, and kids would follow me. . . .” After being denied admittance, Dennis and Ed entered Tangier through the “back door” of the east African city of Cuerta. To procure passage, Dennis tucked his hair under a hat.

Once in Tangier, Dennis purchased a hooded Djellaba robe and sandals – the customary attire of locals. Dennis relates the effect of his travel outfit and hairstyle when entering Lisbon, Portugal: “. . . [W]alking down the street . . . people would come up and kneel in front of me and make the sign of the cross.” Not wanting to be known as Jesus, Dennis quickly mailed the robe and sandals back to the U.S. After visiting Portugal, he and Ed traveled back to Spain. Here, the personal growth and increasing confidence of the young San Franciscan culminated in a decision to separate. Ed had burdened Dennis by forcing him to make all the decisions, so Dennis struck out on his own.

Dennis enjoyed several weeks of solitude and freedom. “I didn’t have much conversation with anybody at any time due to the language barrier,” he explained. When communicating with non-English speakers, Dennis relied on hand motions to ask basic questions regarding food and lodging. Despite his striking appearance and struggle with language differences, Dennis recalls how receptive and understanding people were – a fact that remains impressed on his memory.

Spanish Oranges and Italian Earrings

Dennis continued into Spain, where he grew so ill with a fever and intestinal infection he could only stomach one potato per day. After recovery, he continued to Barcelona and on the way, discovered a welcome drink in the form of orange orchards. Standing on a bridge above, he saw workers picking oranges and called out to them to throw him some. They graciously obliged, and in his customary, matter-of-fact tone, Dennis relates his reaction: “I guess I was appreciative. I picked them [the oranges] up and ate them. They kinda quenched my thirst. . . .”

This generosity continued as Dennis passed through Monte Carlo, Monaco. He met some young ladies visiting from Florence who gave him their college address and promised him a room in Italy. When he reached Italy, Dennis prepared to set up camp on the beach, but a young couple intervened. They told him it was not safe and offered to let him stay in their garage. After a welcome meal of bread and soup, he settled down for a secure night’s rest. He relates his reaction when he passed by the site the next morning and saw the tide completely covering it. “Yeah, I was surprised, and I saw their point. (laughs softly) It was well taken.”

His adventures continued as he journeyed to Florence and found the dignified college campus described by the young ladies. They kindly gave him a room, and one night, while they were all enjoying ice cream, one of them asked if she could pierce his ear. He agreed and afterward bought some gold hoops to display. To this day, he proudly sports a Mickey Mouse earring but has since given the gold hoops to his wife. From Florence, he traveled to Rome and discovered another example of human kindness. Tired from a long day, he was struggling to find a hotel when suddenly an elderly lady appeared out of the crowd, grabbed his hand, and led him to a room. Dennis was very grateful for this woman’s benevolence to a complete stranger.

Generosity of the Oppressed

While in Italy, Dennis decided to travel through Yugoslavia to Bulgaria and Turkey. Upon entering Yugoslavia, Dennis was deeply impressed by the poverty of its inhabitants under the Soviet Union’s dictatorship. He was even more moved by their great generosity in sharing food with him. Dennis comments with conviction, “It seemed that the poorer the country, which was southern Europe, the people didn’t have much, but they were willing to share. . . . I never asked [for] much, other than directions or a place to stay, [but] . . . the ones that picked me up, they would always share their food with me.” When he attempted to enter Bulgaria, the guards blocked his access, but indicated that he would be admitted if he cut his hair. Stubbornly refusing to alter his preferences, Dennis backtracked to the Greek border, where he was denied again. After this discouraging defeat, Dennis trudged down the darkening road, then slithered into his sleeping bag in a ditch. Thinking he was safely out of the way, his heart jumped when he “woke up with an army personnel with a rifle and a police dog, and the rifle was pointed at my head." Dennis quickly gathered his gear and hurried down the road, noting the adjacent airfield surrounded by barbed wire. “I’m not too apt to forget that incident,” he remarks decidedly. Without water, Dennis grew very thirsty as he tramped ahead. He approached some women working in a field and, through gestures, asked for a drink. At that moment, a man on a bicycle arrived with water and gladly gave some to the parched traveler. The string of charitable acts continued with a generous bus driver, who gave Dennis a free ride.

One night, he bedded down in a large, open field of tall grass. He was discovered by some children, all under the age of seven and unable to speak English. Unreservedly, the little ragamuffins presented the stranger with a box of dandelions, which they had spent all day collecting. Dennis remembers with simple appreciation, “. . . [O]ut of friendship, they offered them to me. . . . [It was] something they gave up – something that was theirs – that’s the only gift they had for me.”

Visiting and Escaping Berlin

After sojourning in several other countries, Dennis hitched a ride to Berlin with two English gentlemen. They were forced to procure special visas in order to enter West Berlin through the Hannover corridor. As they prepared to cross the border, a woman with a machine gun inspected them carefully, examined their vehicle, and poked around in their gas tank for stowaways. Once inside West Berlin, Dennis climbed up some scaffolding on the Berlin Wall for a view. While looking down at the guard houses and soldiers, he suddenly heard a bullet whistle over his head and immediately abandoned his perch. “That kinda scared me,” he recalls with a soft chuckle.

Dennis and his English companions also visited East Berlin, and, after successfully navigating through Checkpoint Charlie, they entered the war-torn city. In his journal, Dennis described the decayed buildings, the myriad of bullet holes, and the prominence of policemen posted at every intersection. “Well, it gives you a very uncomfortable feeling with somebody standing around looking at you, so, I told the guys I was hiking with . . . , ‘We spend our money that we had to convert, and let’s get out of here.’ I just didn’t like it at all.” After a depressing tour of the dreary city, Dennis and his companions attempted to reenter West Berlin. The air of oppression choked them and culminated in a problematic border crossing. Although his friends were quickly approved, Dennis was delayed while the guards evaluated his passport. He had lost weight and his hair had grown, which made them suspicious, but after he pulled his hair away from his face and turned various angles, they let him pass. When asked if he was afraid of being detained, Dennis laughed heartily. “Well, I don’t remember. I knew who I was, but I mean, at the time I guess I should have been more concerned than I was.”

Eventually, Dennis parted ways with his English friends and traveled with a fellow hitchhiker to Hamburg, Germany. By far, this was the most memorable aspect of his trip, for in Hamburg, he met the hitchhiker’s friend, Hartwig Schultz. Although Hartwig was in the hospital with heart problems, he arranged for the two travelers to stay with his mother. This short, rotund lady welcomed them in as though they were family, and for a solitary young man, this must have been a very special gesture. Although unable to communicate with her, Dennis relates in his journal how she laundered his clothes, prepared his meals, and guided him gently by the hand. Their relationship was such that he referred to her as “Mama Schultz.” The family took him on excursions to the park and to ride a barge; he even got a haircut from Mrs. Schultz’s daughter, who was a beautician. At the end of his sojourn with the family, Dennis was so touched by their graciousness that he promised Hartwig a place to stay if he ever traveled to the United States.

This visit marked the beginning of the end of Dennis’ hitchhiking. From Germany, he traveled to Denmark and Sweden, where he finally boarded a plane to return home. And so ended his amazing, cross-continental journey. Yet, this was only the beginning of a much bigger life journey. His trip to Europe inspired him in several ways:

Dennis learned to appreciate his immense freedom in America as he contrasted it with the militaristic government in many European countries. He values the security of not living in intimidation and being able to enjoy such routine activities as going to the Post Office and train station without fear. “I’m very thankful that I was a U.S. citizen and not under a police-state control . . . where everything was threatening and everybody walked around with a rifle or shotgun.” After seeing other people living in such oppressed circumstances, he realized how blessed he truly is.

When asked to name a specific life-lesson from his journey, Dennis’ voice warmed as he spoke. “I came back with an attitude that I wanted to do things for other people because I was assisted so many times,” he said. From offering their homes to stay in, to tossing him oranges, giving him a free bus ride and presenting him with a box of dandelions, Dennis discovered the depth of others’ generosity to strangers. “People were truly nice,” he recalled fondly. This spirit of helpfulness was most clearly evidenced in the story of Hartwig Schultz and his family. Dennis relates his gratitude with his words “. . . [T]he family took care of me; they did everything for me and they didn’t know me from Adam.” The impact of their kindness so influenced Dennis, that years later he and his wife welcomed Hartwig into their home when he came to visit at Purdue. Dennis’s wife even drove Hartwig to Cincinnati, OH, where the immigrant became a prosperous U.S. citizen. But Dennis didn’t stop there. After returning to the States, Dennis achieved his nursing degree and has been using it to help people in a psychological ward, nursing home and five different hospitals. Although his hitchhiking journey only lasted for seven months, it has changed him as a person and will continue to impact him for the rest of his life

by Lauren Williams